News

The best never to play for Australia

Cec Pepper was the quintessential wild colonial boy. He blued with Bradman. He lived in a ‘menage a trois’ and willed half his fortune to a woman he’d just met. Author KEN PIESSE introduces the best cricketer never to play for Australia

Those who dared cross Don Bradman had a habit of disappearing. Fast.

Had Cec Pepper been less loud and opinionated he may have been feted forever as a member of the Don’s 1948 Invincibles, the most-celebrated cricket team of them all.

He was an extraordinary talent who could smite the ball over grandstands, zip leg breaks and flippers past the unaware and take screaming catches at slip.

His war buddy Keith Miller rated him cricket’s finest wartime allrounder.

In the Victory Tests in 1945 Miller and Pepper were pivotal in the game’s renaissance in England and beyond after Hitler’s suicide and Germany’s surrender.

Their cricket was skilful, daring and inspired. Tens of thousands flocked in record numbers to once again see England v Australia.

When Pepper hit a huge six into the stands at Lord’s to win the first Test with just two balls to spare, his mid-pitch jig was years ahead of its time.

Within six months Miller the magnificent was representing Australia and with his looks, charisma and sheer magnetism the acclaimed new darling of Australian cricket. But Pepper the firebrand, Pepper the extrovert, Pepper the irascible was in Coventry, a damning run-in with Bradman on the very last day of 1945 effectively burying his dreams of Australian selection.

Having played and travelled virtually non-stop since May, the Services XI was exhausted on its arrival back to Australia but happy homecomings were delayed, especially for those from the eastern States, as the Australian Board of Control announced with little negotiation a series of patriotic matches, starting in Perth on Christmas Eve. Monies raised would go to charity.

There was tremendous excitement when Don Bradman, 37, made himself available for the South Australian fixture. He’d played just one representative game in five years and been invalided out of the Army, spending much of the war incapacitated and at times not even able to raise his right arm to shave.

In Adelaide on the second morning of the match, more than 10,000 Bradman-worshippers appeared, hoping for Australian cricket’s Colossus to make yet another century. Early on, while Bradman was still settling, Pepper twice defeated the Don with his deadly flipper, only for his bellowing, demanding appeals to be rejected.

If the first was desperately close, the second was plumb, so Pepper believed and he flew into a paroxysm of rage. Not only was umpire Jack Scott accused of cheating, Pepper reckoned he was working to a separate set of rules to Bradman, the almighty hometown hero.

Pepper’s torrent of abuse could be heard all over the field. Bradman approached Scott and told him he shouldn’t have to put up with such a tirade. It was totally against the spirit of cricket. These matches were supposed to be friendlies. Bradman made a century and Scott laid an official complaint against Pepper for his ‘continued filthy language’3and his card marked, especially when a promised apology was never received.

‘I got the little sod out twice in one innings and the umpire wouldn’t give him out,’ he said years later.

‘When I told the umpire what I thought of his decisions I was expected to apologise. I wouldn’t. And I came to England.’

In 1950, Bradman admitted that Pepper had shown ‘every sign of being a great player’. His flipper was both lethal and mesmerizing. ‘He could make the ball turn from the off by some unique method of delivery which even now remains a mystery to me.’ The Don regarded only one other wrist spinner to be superior, Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly.

Having walked out on a Test career Pepper became the highest paid cricketer in the world and in the next 15 years dominated professional cricket ranks in and around Lancashire.

So good was ‘Pep’, Frank Tyson once claimed, that he could turn a game in 10 minutes — a little like Shane Warne. They had opposed each other at Lancashire League level, Rochdale versus Middleton, 16-year-old Tyson nervously surviving a maiden over without laying bat on ball. Relieved to hear the umpire call ‘Over’, Tyson looked up to be confronted by the hulking figure of Pepper: ‘You can open your bloody eyes now son.’

Pepper’s salty language and ferocious appealing was often as colorful as his strokeplay.

He was a headliner everywhere he played, most committees prepared to overlook his larger-than-life ways. No one could pull a crowd like Pep, hit as extravagantly or take a wicket when it was most needed.

League historian Noel Wild called him ‘a batsman’s living death’ and ‘simply an incredible, enduring character’, who as a 43-year-old was still good enough to take 120-plus wickets in a League season. A young Basil D’Oliveira said even into his mid-40s Pepper hit the ball ‘like a shell from a field gun’.

League historian Noel Wild called him ‘a batsman’s living death’ and ‘simply an incredible, enduring character’, who as a 43-year-old was still good enough to take 120-plus wickets in a League season. A young Basil D’Oliveira said even into his mid-40s Pepper hit the ball ‘like a shell from a field gun’.

Of the Australian’s renowned temper, Eric Denison, a long-time Lancashire League professional said: ‘Something is bound to erupt and it’s usually Cecil George.’

Sydney historian Max Bonnell believed Pepper played the game with ‘unrestrained and sometimes tactless competitiveness.’

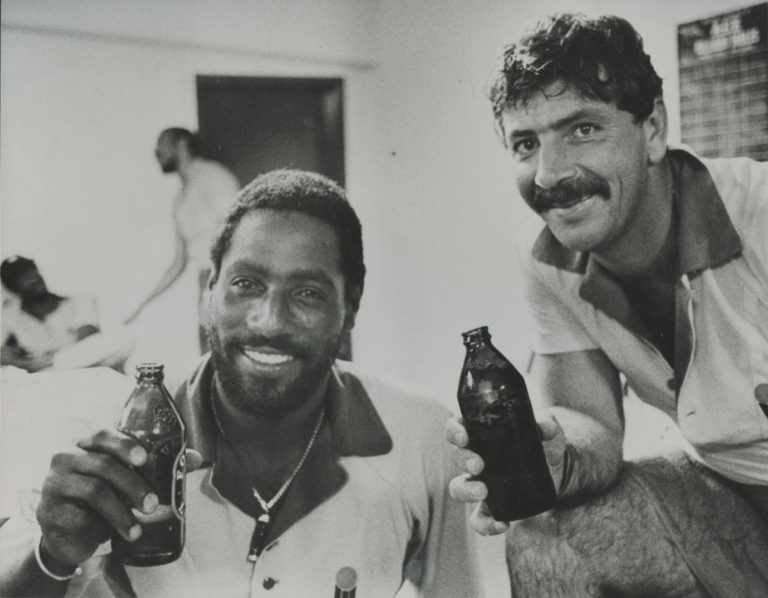

He was also amazingly generous and loyal to his friends. He shared match-day collections, he bought a young and penniless Frank Worrell a car when he was studying in Manchester. He’d pick up the tab for his teams on their end of season trips. He was at Collie Smith’s bedside the night the West Indian champion tragically died after a car driven by Garry Sobers hit a 10-ton cattle truck. He paid off Sobers’ gambling debts. As a first-class umpire for 15 years he’d coach rookie bowlers on where they should pitch the ball to take a wicket.

Pep had more friction in his life than most. He had three children with three different women. When his eldest contacted him, having finally found out that Pepper was his father, Pep wondered if he was coming for 40 years of maintenance monies. Another son changed his name by deed poll within days of turning 21.

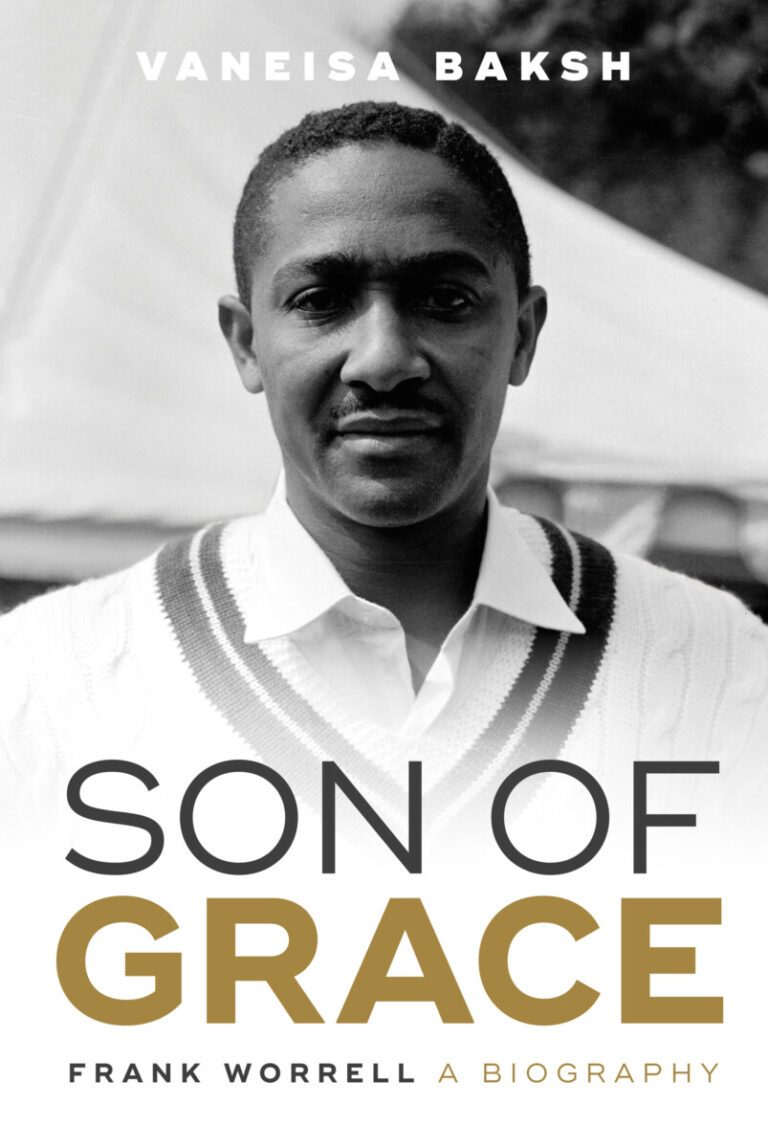

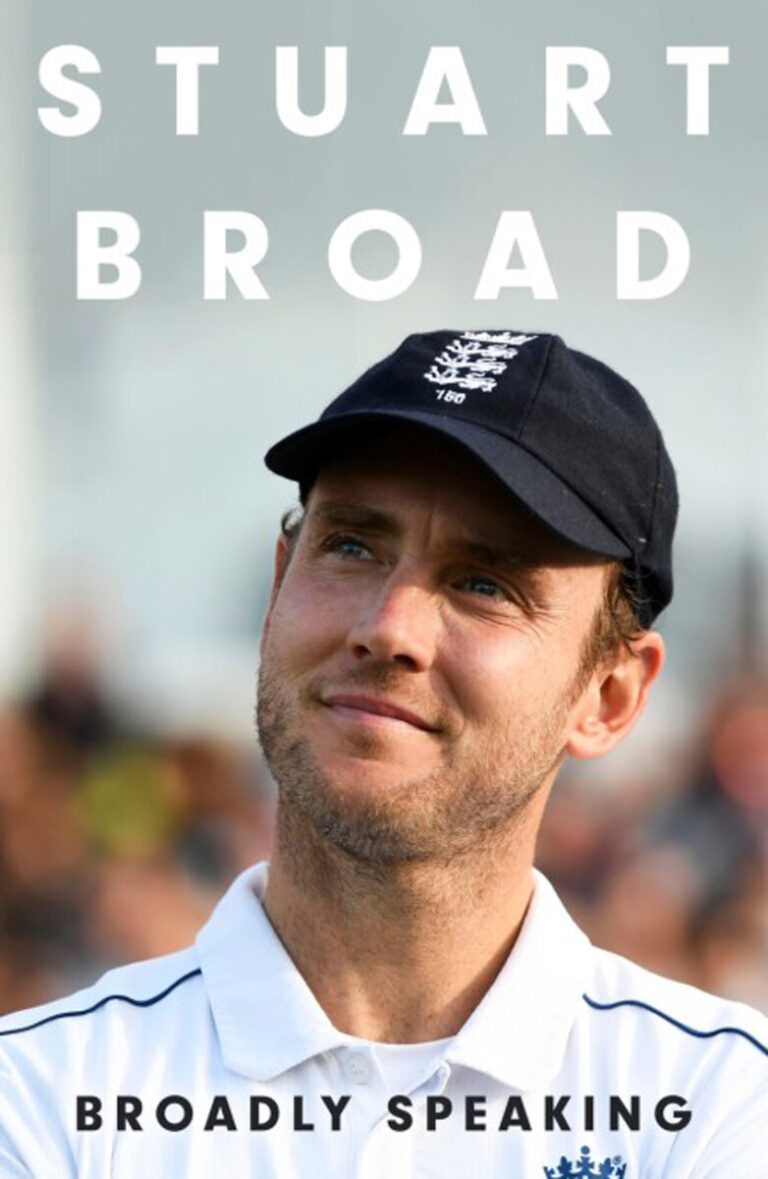

Excerpts from Ken Piesse’s latest book, Pep, the story of Cec Pepper, the best cricketer never to play for Australia... Pep is available now in both hardback and softback from cricketbooks.com.au